Martin Luther Pink

Several days ago, a friend’s Facebook comment got me to thinking about the word pink. I like pink. And pink things. Probably to a  fault. I still daydream about a pink-rhinestone-covered stapler a former colleague had. I have pink pillow shams, lots of pink clothes, pinkish boots, a pink flashlight, and a pink lampshade. I can’t resist snapping photos of pink sunrises and sunsets from my hilltop home. I need a new pink purse because I’ve worn out the last one. I even made the instruction cards in my first InSight Words deck pink.

fault. I still daydream about a pink-rhinestone-covered stapler a former colleague had. I have pink pillow shams, lots of pink clothes, pinkish boots, a pink flashlight, and a pink lampshade. I can’t resist snapping photos of pink sunrises and sunsets from my hilltop home. I need a new pink purse because I’ve worn out the last one. I even made the instruction cards in my first InSight Words deck pink.

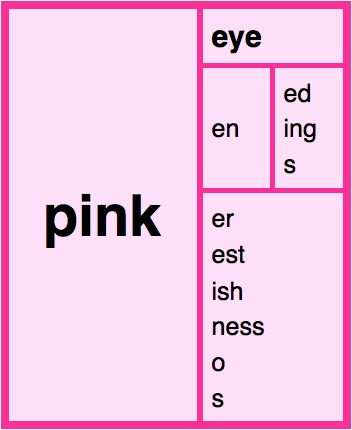

So the word was stuck in my head for a few days, which means it had to be investigated if I had any hope of accomplishing anything else. It turns out there are no fewer than seven different base elements spelled <pink> in English:

- The color pink is named for the flower.

- The flower (Dianthus) may be named for its ‘pinked’ edges (perforated or punctured) — think pinking shears. Or it may be named for pink eyes — not conjunctivitis, mind you, but an early Modern English phrase on loan from the Dutch pinck oogen, ‘small eyes,’ — referring to the flowers’ appearance reminiscent of small, half-closed eyes. The pink in these pink eyes doesn’t historically refer to the color, but to size.

- The first hypothesis for the flower’s name, it’s ‘pinked’ edges, is its own etymological wild goose chase. Found today mostly in reference to sewing or design, this <pink> may be related to Germanic words like peck, pick, and/or pike, or to Latinate words like puncture, poignant, pungent, punch, and pugnacious.

- The second hypothesis for the flower’s name, pink [‘small’] eyes, works well as a translation of the French synonym oeillet, a ‘little eye.’ The Dutch word pink has a historical denotation of ‘small,’ and is used to refer to the pinkie (or pinky) finger, whence the English name for the littlest manual digit.

- The ‘small’ sense also shows up in the name of a pink, a fast, nimble little watercraft common in the Atlantic ocean during the 17th and 18th centuries. The Spanish pinque and Italian pinco also reflect this Dutch derivation.

- Some folks say an engine knocks and pings; others, mostly Brits, say it pinks.

- There’s also a dated term pink that refers to a kind of lake (lacquer) pigment, but it’s yellowish and of uncertain origin. Go figure.

The pronunciation of pink is worth paying attention to: #6 is onomatopoeic, and #3 belongs to either one or another family of words that also kind of sound like what they mean: pike, pick, and peck, or puncture, punch, and repugnant (literally, something that ‘punches back.’) The word pink has a nice ring to it. It’s sharp and tingly and saying it makes you smile a little.

Pink has a straightforward orthographic phonology, too: it has four graphemes <p i n k> and four phonemes /p ɪ n k/. The phonetic realization of those four phonemes, however, sends a lot of folks into quite a tizzy. The /n/ is realized as a velar [ŋ] because of its coarticulation with the velar /k/ — the same thing happens in words like distinct or banquet, but few phonics programs address [ŋ] beyond monosyllables. The /ɪ/ is nasalized, and often raised by the velar coarticulation too, so it ends up feeling more like an [ĩ] — a long, nasal eeeee. That’s the part that makes you smile.

Traditional phonocentric approaches teach this and other velar nasal patterns as whole rimes (ink, ank, onk, unk) and giving them made-up names like “welded sounds” or “nasal blends,” rather than taking an accurate look-see at the orthographic phonology. Instead of studying the phonology of <n> — which can be realized as [ŋ] before a velar consonant — these approaches add to the cognitive load for each child by piling eight new patterns (including ing, ang, ong, ung) into the mix, and often not clearly identifying them as rimes and not as graphemes or as that phonics horror of horrors, “blends.” This is largely because phonics is so stuck in its misapprehension of the phoneme that it can’t deal with the difference between the /n/ phoneme and the [ŋ] allophone. [I’m happy to consider an argument that there is a /ŋ/ phoneme, but it has to present an accurate understanding of the difference between a phoneme and an allophone.] Another phonics problem I’ve observed time and again is the failure to differentiate between an <ing> rime and an <ing> suffix. This distinction is a non-negotiable understanding in orthographic study: the same sequence of letters doesn’t always bear the same identity or the same function. It depends on which word they’re surfacing in.

My spelling teacher (who happens to be French) always says that there are no coincidences. As I was working on this pink-inspired piece, I spoke with a colleague who told me about a 3rd grader she works with who has a very hard time with the inks anks onks and unks of her Wilson Reading System instruction. The child reads words with these rimes just fine in connected text, but not in isolation. I bet you a dollar that she’s trying to “sound them out” and is trying to string [p ɪ n k] together, for example, but can’t make sense of it without a meaningful framework. My question — my colleague’s question too, which is why she contacted me — is What in the heck is the goal of “reading” words in isolation if she can read them fine in text?

I can’t answer that in any way that I can argue has the child’s best interest, her engagement with language, or her lifelong development as a literate soul, at heart. The bloom is off the phonocentric rose.

The phonology only has structure in a meaningful framework, which word lists really never provide. The ways in which <pink> makes meaning are interwoven with each other and with our history. According to Oxford, the use of pinkie for ‘little finger’ was reinforced by the color sense (#1), but of course, that only works well for pasty Celts and Anglo-Saxons, not across the English-speaking world. The association between the flower, color, and flesh is also reflected in the word rose (think rosy cheeks), but especially in the name of one kind of dianthus, the carnation. In late Middle and early Modern English, the Latinate words carnation and incarnation were used to mean ‘the color of flesh,’ anything from ‘blush-color’ to ‘blood-color.’

Again, this whole pink-flesh connection only really works, at least on the surface, if you’re a white person. Oxford points out that not all carnations are pink, so of course not all dianthus are pink. Likewise, not all flesh is pink. I’d say Duh, English, but the French did it first.

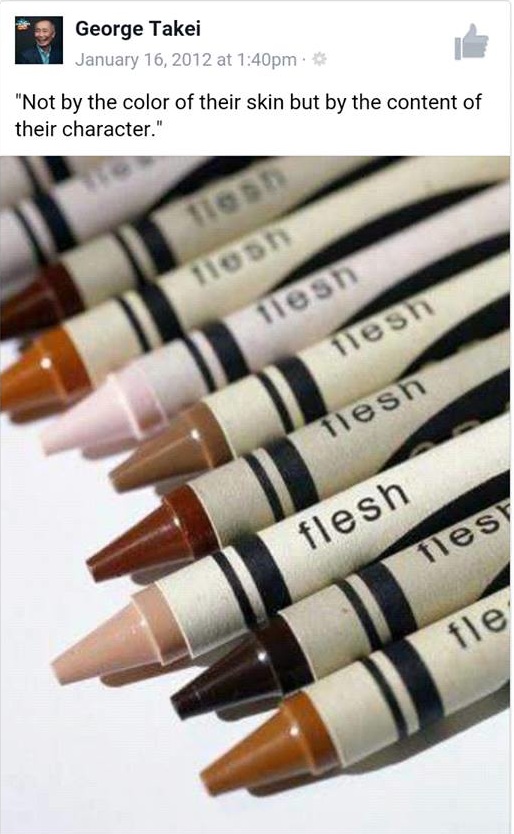

I’ve also learned from my spelling teacher that the study of the writing system necessarily and organically brings about the possible study of so much more. What does it mean, in a world where we argue about whose lives matter, that the historical association of pinkness with human skin is captured in our written language? How would today’s third-grader respond to the information that my childhood Crayola box had a pinkish crayon labeled “Flesh,” but hers does not? What might a study of words like white and black reveal to us? I’m not interested in this because I had some social studies agenda in mind when I started studying pink; rather, these questions are where the study of pink led me. Just in time for Martin Luther King Day and everything.

I wrote that. Then I saw this:

There are no coincidences. That’s not some kind of mystical statement; it’s an observation. There are no coincidences; there are the connections that we conceive of, the stories that we tell, and the meaning we make.

Tickles me pink.

10 Comments

Lovely post! (Of course, I *am* fond of all kinds of dianthus).

Carnations have always been my mom’s favorite.

Loved this Gina. And I have to add another connection. I’m sure your readers will delight at the link between the words “carnivore” and the flower the “carnation” that Grade 1 students of Lyn and Jim Anderson in Indonesia taught me with the video at this link:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=53iJ4AnMRLU&feature=youtu.be

The evolution of these words were evidently before that great image of the beautiful diversity of “flesh colours” in the Crayola box.

That’s just it — their history tells us about who we’ve been and who we’re becoming.

Enjoyed this post, and I’m not particularly drawn to pink — at all. xo

We are having the same issue with the Wilson welded sounds!

I have read this post several times and I always enjoy it and find myself smiling while I read it. Honesty mixed with wit! It’s so nice to be able to makes sense of at least some things.

[…] <er> suffixes), liter, arbiter 9. islank: island, mislay, Islam, mankiller, and anyhow, vowel pronunciation is often disputed before [ŋ], but the orthogaphic phonology is revealed by the graphemes. 10. polonel: colonel, colony, colon, […]

*ink, ank, onk and unk.

I’m not an answer-factory, and I don’t plan lessons for people. The answer to the question “how do I teach this” is always “honestly.”

There is no such thing as *the “ing” sound.