Spirit Animals

I am ridiculously excited to welcome two new companions to my study circle. The first time I meet with a child for the first time, I always ask them what their parent has told them about our meeting.

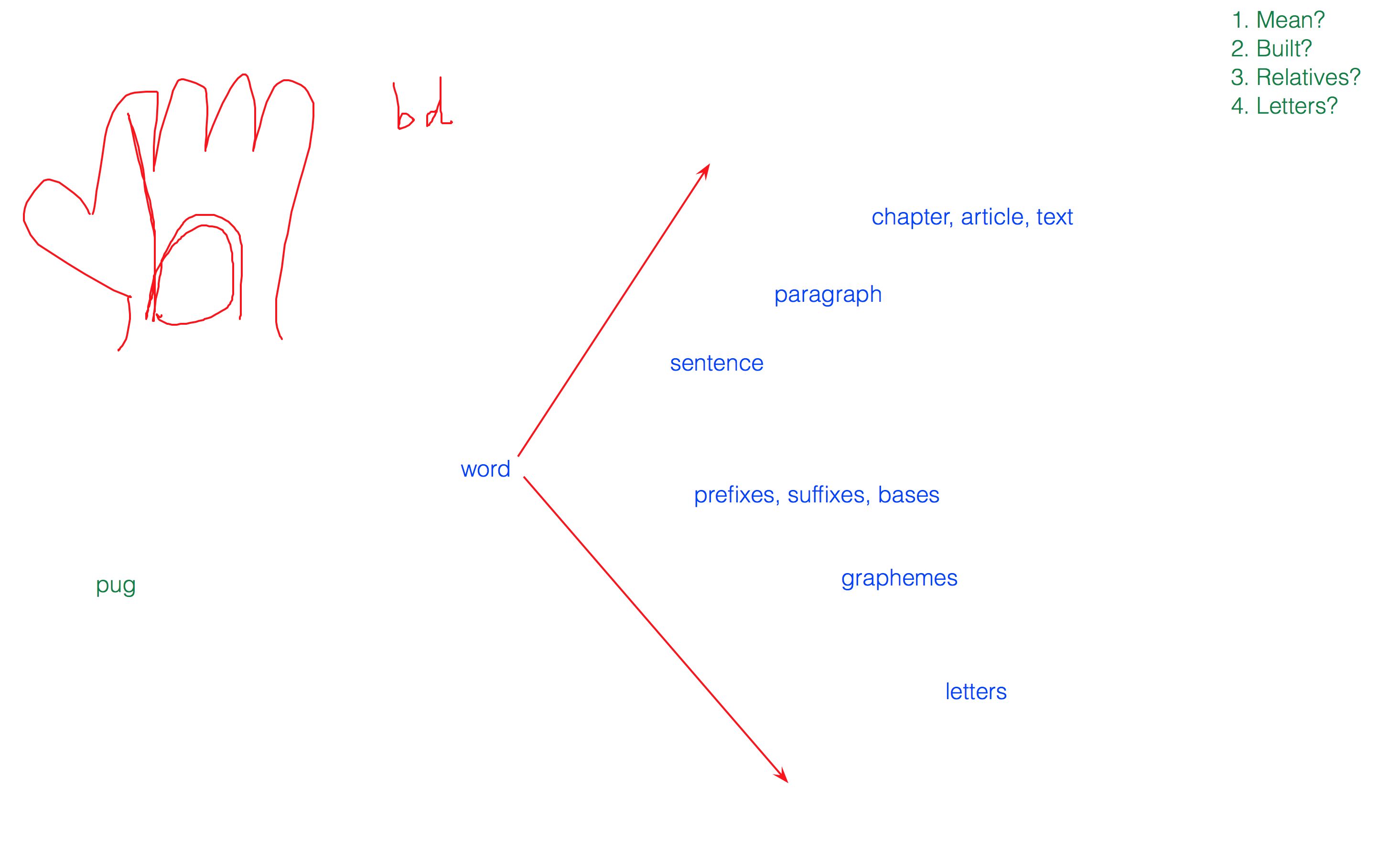

Wynn identified me as a linguist. I asked him what a linguist studies, and he said, “Words?” So I showed him that yes, we can study words, but we can also study structures larger than words and smaller than words. For any of those structures, we can consider how it’s built, where it came from, and what it is and is not related to.

Wynn is a 5th grade boy who is a non-writing avid reader who loves history and his pug. He’s not the first adolescent boy who snugged his pupper during our whole online session; my ‘in’ words with other boys have included both dachsund (German for ‘badger-dog’) and cockapoo (a portmanteau of cocker spaniel and poodle). Next time I meet with Wynn, we’ll study pug. I have no idea where that word came from: Was the pub named for its nose? Or was the nose named for the dog?

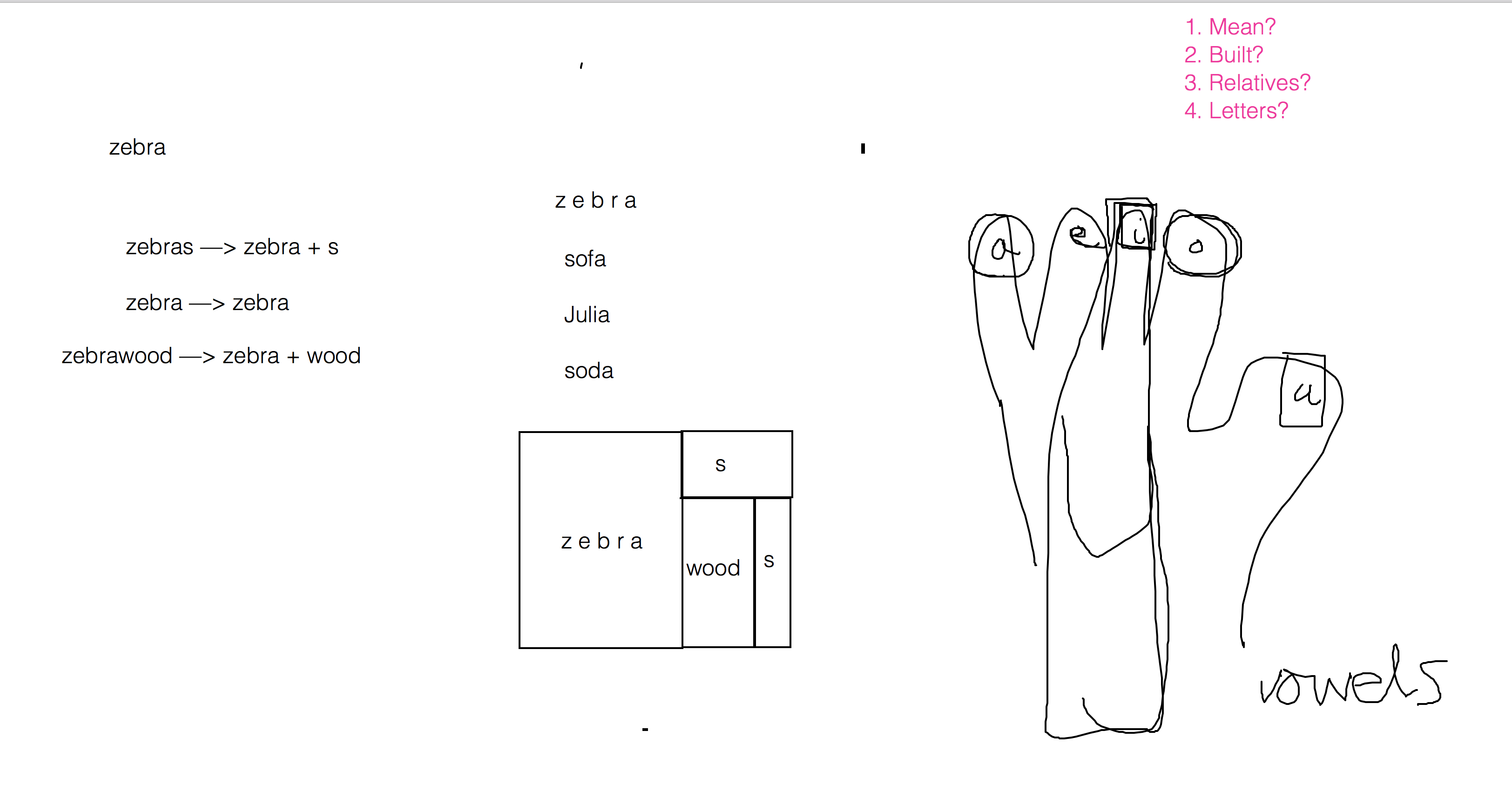

Zebra is a 2nd grade girl who pegged me right away as a “word specialist” and who loves, well, zebras, of course. Zebra and I both love pink and glitter, so we totally bonded.

She already knew that < a, e, i, o, u > and sometimes < y > are vowels; I told her that lexical words that end in < a > or < o > are not native English words. She had a hunch that zebras were from Africa, so we looked at the history of the word, and found out that it is indeed foreign, just like the thing it names. We built a house for our word family, also known as a matrix, and we practiced a couple of word sums.

I also told Zebra about my other study partner Cupcake, who loves pandas like a crazy person. When I was that age, it was koalas. Hey! Look! All those animal words end with < a > and name animals that are not native to England and do not have native English names!

Animals are an inspired way in to language study for so many kids. Even the word animal is itself wonderful and revealing to study, for those who aspire to an understanding. The wonderful ways that humans have named their animal companions make for fascinating study, and that study can really breathe new life into how kids understand and are motivated to understand their writing system.

Over the past several years, it has been my pleasure to offer Dave Buchen’s Why is a Tiger a Tiger, as it provides an almost conspiritorially enticing entry into etymology for any kid who resonates with animals. LEX kept that book alive in a second edition after the first went out of print. Dave recently informed me that he is doing a Spanish version of the book, and will be publishing both on his own later this year.

I will continue to sell the book through this year’s Etymology conference; order yours now so you don’t miss out! You never know what will transpire.

1 Comment

Another lovely account of the learning in your tutoring sessions Gina. It may seem obvious, but I love the emphasis on finding that “in” word with a student, and that it is so unimportant which word that is. One fun story like that for me was a student that I had worked with a few times via video conference, but I had not felt I had got the engagement I was looking for. I tried, but failed to get him to share with me what his own interests were. After a couple of on-line sessions we had the opportunity to meet in person because I came to his town for a workshop. It was the conversation “before we started” that provided the key. He had flown to the city with his mom and on the way he got the chance to go into the cockpit and talk to the pilots. It became clear he was a freak about planes. We ended up thinking about the word “cockpit” which had never occurred to me before. We went to Etymonline and instantly the engagement and interest in investigating words changed.

Who would predict that the word “cockpit” would be the logical place to start for someone who was in serious crisis for reading and writing?

That’s the problem with even trying to predict which words are best to study! Typical instruction would have this kid working with controlled text that would “protect” him from the word that got him going.

When I tutor with students, parents often are keen to share files of reports from psychologists. I always tell them please don’t and promise that if they do, I won’t read them. Whatever information they hold won’t change what I do. I’m going to respond to the learner in front of me and identify what they do and do not seem to understand about their writing system, and go from there.

The ONE thing I do ask them to do is to send me information about what their child loves to do. That’s going to offer a conversation about that kids interest that will present a word from his world that we can dive into.

There is much more in your post that this — but I wanted to highlight your observation about how important it is to work with the interests of the learner. This also highlights how unimportant (in fact seriously problematic) it is for instruction to be framed around pre-selected words.

After all, since the spelling of every English word is organized by the same orthographic conventions, every word has something to teach us about how those conventions work.