Phonics and Other Phour-Letter Words

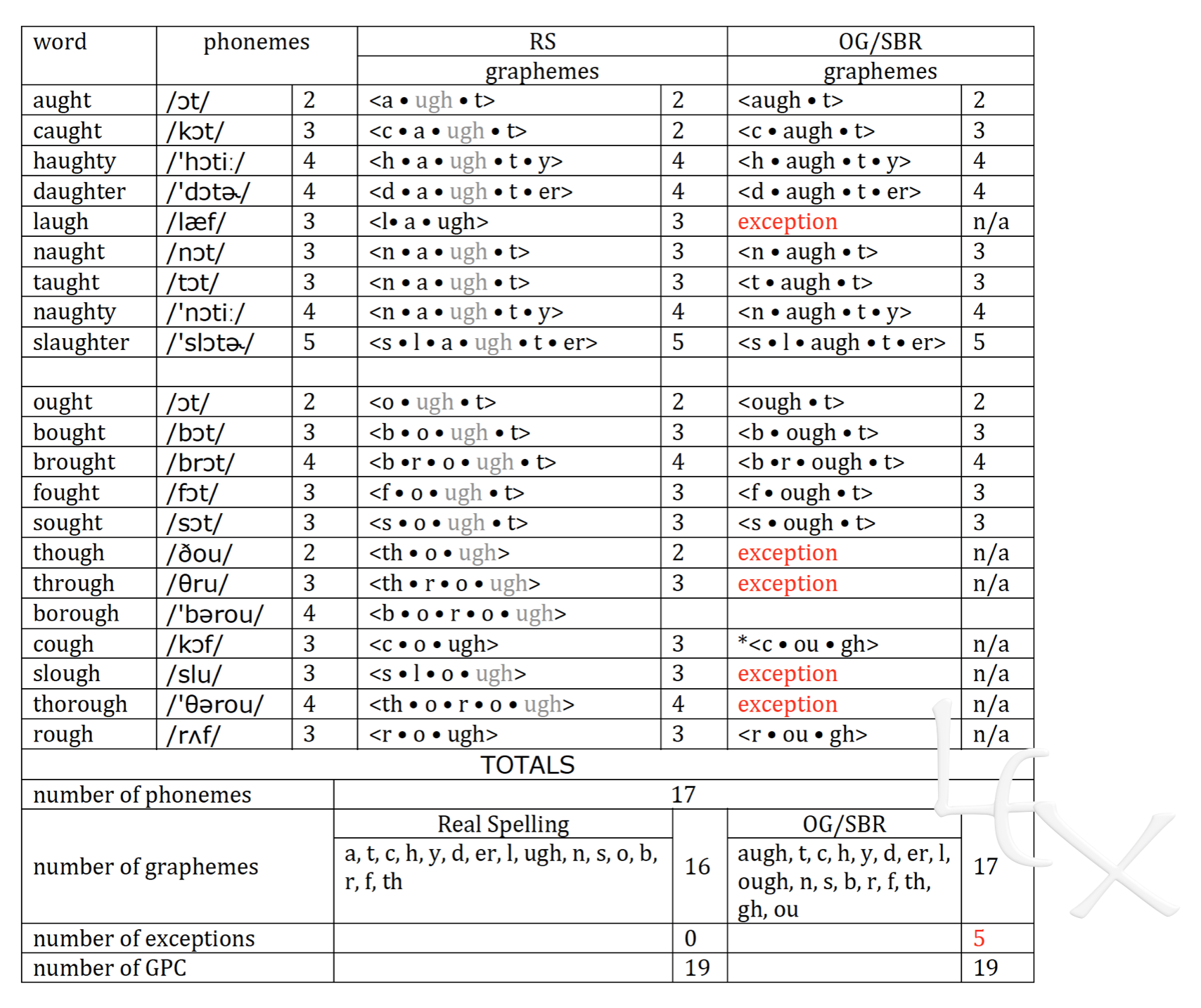

One of the ways that my understanding is a life-changing improvement over phonics is that I can prove that there are no four-letter graphemes. All the phonics people — really, everyone — believe that *<ough>, *<augh>, and *<eigh> are graphemes, which they call *quadgraphs. This false conceit often requires people to accept that an *<ough> can spell a bunch of different “sounds,” including vowel-consonant combinations like [ʌf] in rough or the [ɔf] in cough. Or else it comes with a list of 19 or 20 “exceptions.” Seriously — look at your own phonics materials and you’ll see what a convoluted explanation is offered.

In real life, there’s a consonant trigraph <ugh> that spells [f] and a vowel trigraph <igh> that spells [aɪ], and they can both also be etymological markers, spelling nothing at all. Today, a really sweet woman who is new to studying with me asked me to tell her where she “can locate information about quad-graphs not being truly accurate.” She has ordered materials from me, though they haven’t shipped yet. And she told me that she’s already watched this film, but she asked to read a written explanation somewhere. So instead of writing a response directly to her and her alone, I’m writing this for everyone, especially for me, so I can point people here in the future.

So, what’s wrong with calling *<ough> and *<augh> and *<eigh> *quadgraphs?

For starters, there is NO SUCH WORD as *quadgraph.

It’s not in any dictionary I checked, and if you google it, it shows up ONLY on phonicky websites, because the term is made-up phonics gobbledygook. I think it was Louisa Moats who started that garbage; at least, hers is the first writing I can locate it in. But it’s abject nonsense, and here’s why:

There is no Latinate morpheme *<quad> that can be compounded with the Greek base <graph>. Any modern English word quad is a clip some other word, like quadrilateral or quadrangle or quadricep or quadruplet, depending on the context, just as flu is a clip of influenza and lab is a clip of laboratory. But in no way is <quad> an element that means just plain old ‘four.’ Some people use the term quadplex instead of quadruplex, but the former was invented in 1946 and has largely fallen out of use, compared to the normal compound.

The real Latinate base element that denotes ‘four’ is <quadr>, as we can see in the sums for the following real words:

< quadr + i + lateral >

< quadr + angle >

< quadr + ant >

< quadr + u + ple >

< quadr + i + cep >

Therefore, if we needed to invent a hybridized Greco-Latinate word to denote a 4-letter form, we’d have to invent *<quadrigraph>, which is also not a word:

Now, it’s true that sometimes, a modern scientific understanding does demand the invention of a word, and sometimes a hybrid is called for. For example, the purely Greek compound telescope was already around when a new distance-seeing device was invented in the 20th century, so we called it a television instead.

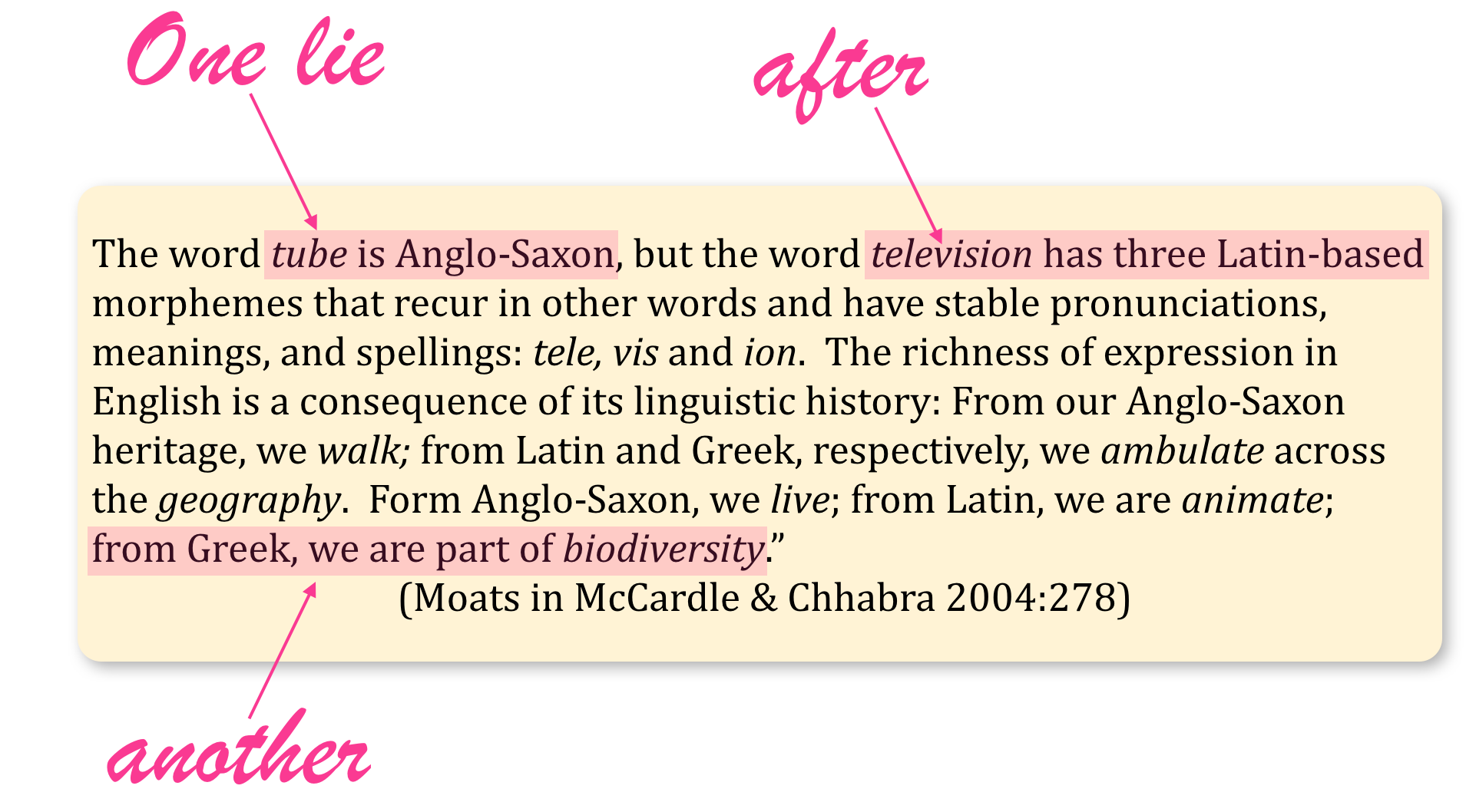

Unfortunately, so-called *quadgraphs are not the only lie Louisa Moats tells. She also falsely (and laughably) claims that television has “three Latin morphemes.” It doesn’t. The first one is Greek. Another example of a modern hybrid is biodiversity, which Louisa thinks is “Greek,” isn’t. The bio parts are Greek, but diversity is Latin. It’s a modern concept with a modern, hybridized name. I promise you, the ancient Greeks and Romans were not discussing televisions or biodiversity. The best part is that these two examples of mendacious etymuddle – along with a third — appear in a just half of a single paragraph from Louisa, in a so-called piece of “reading science.” Look:

This is how it works: Louisa lies to teachers, and teachers pass those lies on to kids. And YES, I DO mean to use the word LIE, because when you say you are writing something that is “scientific research” and you don’t bother to even look anything up before you make your claims, that is not an ethical approach to professional publications. If it were one mistake, it’d be one thing, but it’s like this every time she tries to write about etymology. It’s a pattern of careless deceit, lying by omission.

How is this “science”? Why should we trust the “science” promoted in this book and others like it?

Also? Tube is Latinate, not *Anglo-Saxon. Intubate, tubal, tubular. You don’t even have to look it up — you just have to think beyond a single example. You know, like a scientist.

I digress.

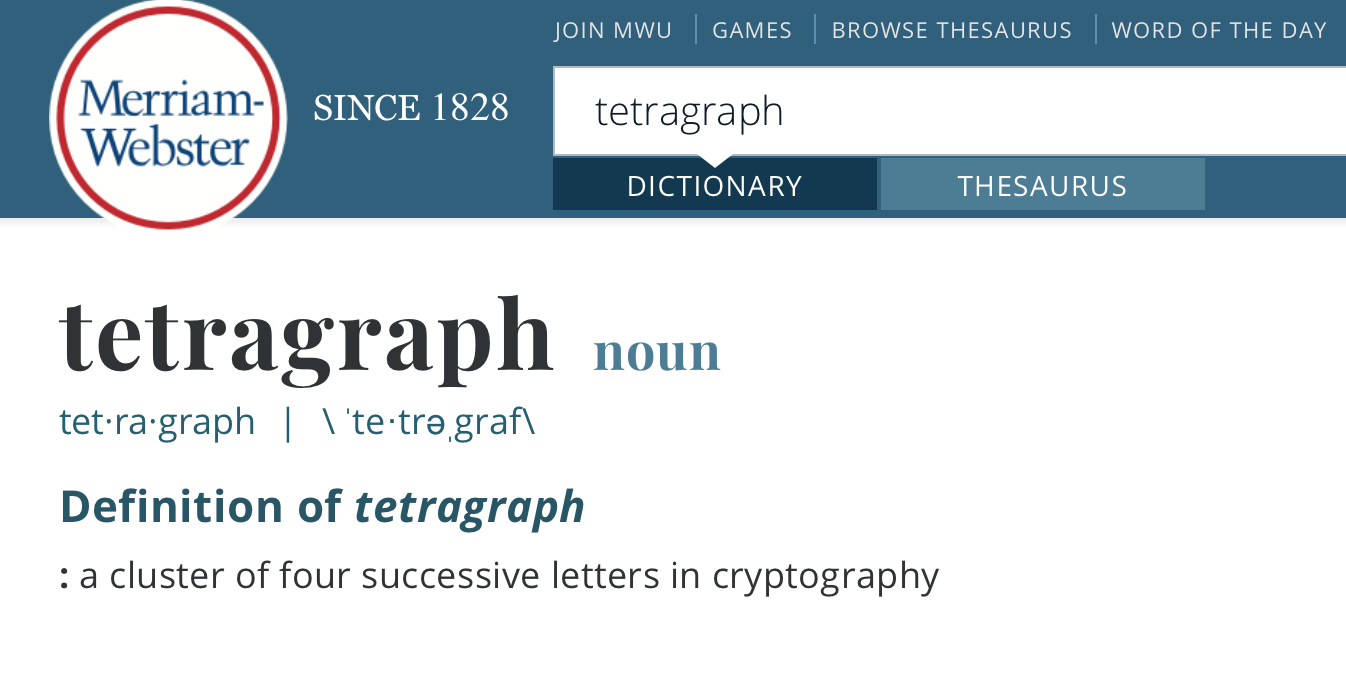

So anyhow, the fact is that there is no need whatsoever to invent a hybrid term at all, since there is already a perfectly good word available to us: tetragram, or tetragraph. The <tetra> derives from the Greek word for ‘four,’ as any self-respecting Tetris-playing linguist can tell you. Traditionally, the term tetragram has been used for a four-letter word, so in recent years, tetragraph has emerged as the orthographic term to follow digraph and trigraph. It’s a real word, attested, in a dictionary and everything:

A decade ago, when I was an OG trainer and newish to this understanding, a colleague and I attended a workshop with Pete Bowers in Chicago. He briefly made reference to the <ugh>-not-*<ough> elegance in his talk. Someone asked about it, and we spent a few minutes looking at examples, like <l a ugh> and <th o ugh>. One of the attendees was Susan Hall, who had been invited to attend for free. She had been a co-author with Louisa Moats of a couple books for parents, but by the time of this workshop, she owned The 95 Percent Group. When she stood up to leave the facility, she announced to my colleague and me, “Well, I’m not giving up my *<ough>!” I’m not even kidding. No evidence, no reasoned dialogue. She just took her *<ough> marbles and went home.

The 95 Percent Group made close to $9 million last year training people in the teaching and testing of phonics. Read the reviews.

Likewise, on Twitter, and elsewhere, I have piles of people who have never studied with me, never read a word I wrote anywhere other than Twitter, who deliberately refuse to see the elegant logic of a <ugh>, clinging to their clumsy *quadgraphs like a lifeboat in a phonics shipwreck. “Well it’s not very common,” they say. But a <ugh> is BY DEFINITION more common than either <augh> or <ough>, so if commonality is the goal, <ugh>’s your gal. “But it only appears after an <a> or <o>,” they say. SO WHAT? Lots of graphemes have place-value restrictions. We avoid a <j> after an <i>; an <ay> is final; an <aw> can only be followed by <n, l, or k>. A <wh> is only initial. Clearly, phonics can’t logic. They allow that a <ph> is etymologically driven, but scoff when I suggest the same is true of an <ea>.

It’s amazing to me that people who argue so constantly and ubiquitously for teaching “Grapheme-Phoneme Correspondences” über Alles will also vociferously resist understanding actual how actual graphemes correspond to actual phonemes. Like, they actively and deliberately refuse to see what I show them.

I learned about the <ugh> from the work of my orthographic linguistics teacher, and I started writing about it myself in 2013. I pinned an analysis to the top of my Twitter profile. Here’s the first, quite comprehensive analysis I did in 2010:  I’ve laid out the proof time and again since then. In my LEX Grapheme Deck. In my classes and live workshops. In Facebook posts.

I’ve laid out the proof time and again since then. In my LEX Grapheme Deck. In my classes and live workshops. In Facebook posts.

Why use a <ugh> instead of an <f>? Because, a <ugh> can be related to [k] or [g] or [ʧ] in a word family, but an <f> cannot. An <f> has a different set of relatives: <p, ph, b, v>. Again, I lay all this out, with evidence, in my LEX Grapheme Deck. That deck has been published for a decade and no one has falsified anything in it yet. Not One Thing.

Likewise, there is no *<eigh>, nor *<aigh>, the latter of which never gets mentioned in phonics, so obviously phonics really doesn’t have it their facts straight. What there is is an <igh> etymological marker that marks a relationship to a /k/ in related words: eight~octave; weight~vector; straight~streak. Phombies will conjecture at me until the cows come home about whether kids “need” to learn this or whether this understanding is “useful,” but they will never ask themselves the same question about their ham-fisted *quadgraphs.

No one has ever provided me with any evidence, any analysis, that proves that English has tetragraphs. Phombies are moving targets. I ask them for proof and they jump around from non-sequitur to non-sequitur, mumbling about how common or uncommon they imagine something to be, or quoting some phonicky source, but citations don’t prove anything. They’ll lament that the <ugh> I’m positing spells “several sounds” — as though that were an objection to anything! Because how many “sounds” does their beloved *<ough> mutant have? Anyhow, that’s false. A <ugh> can only spell one single phoneme, and that’s [f]. Otherwise, it spells nothing at all. People get really fixated on this, and then they scold me for using what they call an “uncommon” example.

But in a decade of speaking, writing, publishing, teaching, and presenting the proof for the <ugh>, no one has ever been able to falsify it. Here’s what I told my new client: “The thing is, [New Client], it’s not up to me to prove that *quadgraphs are inaccurate. Rather, it’s up to YOU to prove or find proof that they are accurate if you want to use them.”

Even Wikipedia knows that “English does not have tetragraphs in native words.” In fact, it doesn’t have any at all. When even Wikipedia knows more about English spelling than so-called “experts,” well, that’s rough.

9 Comments

Oh! For some reason I was under the impression that etymological markers were something DIFFERENT from zero allophones…but the more I started seeing zero allophones, the more I was wondering what was left to be an etymological marker. This post is really pushing my understanding on this front. Thank you!

Etymological markers and zero allophones *are* different.

Etymological markers zeroed diachronically, or were added in error.

Zero allophones zero synchronically, but not always.

It’s a critical distinction. People who study with me and understand it are glad they do.

Ahhh–will keep looking out for Science of Silence and/or Zero Allophone to hit the schedule! Thanks, Gina!

Thank you so much for this blog; I have read and reread it many times already! There is information here that has peaked my curiosity to continue my research as well. Love the journey! And thank you again for taking the time to share your expertise!

Thank you, Gina. That “eigh” card will be permanently removed from my Scottish Rite and Alphabetic Phonics grapheme decks. I have studied with the linguist you mentioned in your blog since I met you at the Orthography Conference last April in Dayton. He teaches “ugh” as being Old English in his Real Spelling videos. (Please, everyone, watch them. They are a wealth of information!) What you both have shared with me fascinates and helps me be a better therapist. Thank you both for aiding my joyous and amazing journey.

Gina, Thank you, for taking the time to write this article. It is amazing! I am blown away with the in-depth information you shared. It made me interested in learning more about grapheme-phoneme correspondence, etymological markers, their relationship to phonemes and graphemes, and all other orthographic structures that are out there.

Thank you for reading it!

Can the word “quadraphonic” be used to represent those 4 letters sound like “eigh”?

Not even remotely. Why?