Bright Ideas

I rarely post here since starting my Shameless Spelling site, and mostly what I post here is announcements and updates. I will, first, get two quick updates out of the way: First, in case this is the only place you follow me, I finally earned my Ph.D. in late 2022. I defended my dissertation in October, and graduated in December. I am enormously relieved, and grateful to everyone who supported the effort. My dissertation is embargoed for four years in order to attempt to publish it, so it’s not currently available to read. Stay tuned to the usual channels (including this one) for information as it becomes available.

Second, I am still working on Sixty-Five Weeks, as it is a behemoth undertaking. It is now evident to me that in addition to (a) my unexpected family obligations over the past several months, I also grossly underestimated (b) the actual amount of time this particular research and development would take. Your continued patience is appreciated, and I do not take it (nor your financial investment) lightly.

The main reason for this post, however, is to share some good languagey resources with you. I was planning to post this on Shameless Spelling, but that site is currently undergoing some unexpected maintenance, so I decided to share it here instead.

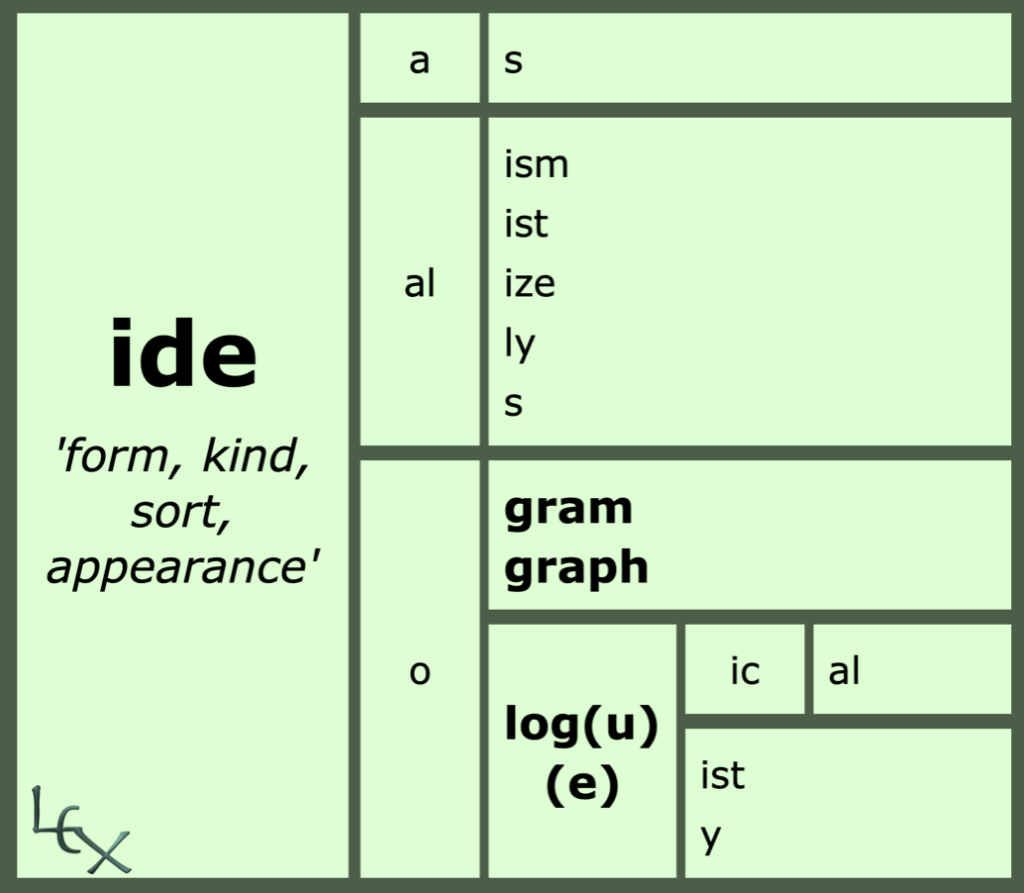

A teacher friend has a kiddo who recently asked about the word idea. Notice that there is no <ea> digraph, because each vowel letter is itself syllabic, pronounced separately. I put together some study resources for them, and decided to share them with all y’all as well. Here’s the immediate family for the bound Greek base element:

Note that the base element’s final <e> is syllabic, not replaceable. That’s common enough in elements of Greek origin, like the <home> in homeopathic, or the <ope> in calliope. I could’ve added ideate and ideation and probably a handful of other words to this matrix, but I didn’t.

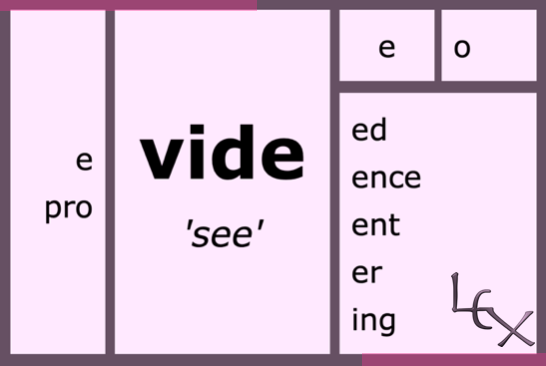

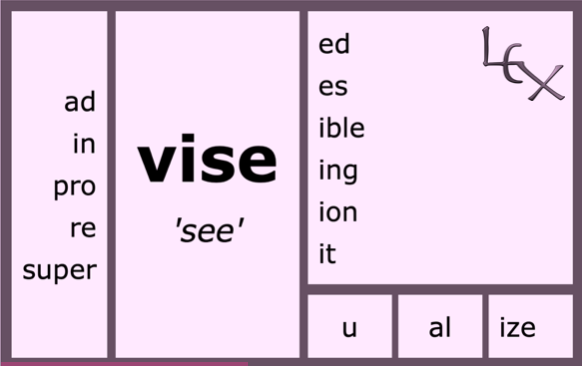

I also shared matrices for some of the Greek <ide>’s Latin cousins, the bound, twin base elements, <vide> and <vise>:

“These base elements are connected to the same PIE *root, which you can find in Etymonline,” I emailed my friend. That is, along with the native English words wit, wise, and wisdom, and some choice French words as well. In fact, it’s a sizable extended family, which I put together into this big ol’ picture:

“There’s lots to notice here,” I told her. Depending on the kiddo(s), you can decide how much or how little of the following points you’d like to study with them:

“(1) the initial <v> in the Latin forms would’ve been pronounced [w] in Latin. It only became [v] in French.

“(2) the Germanic forms have either an initial [w], or a velarized [g], which was probably originally [gw].

“(3) The Greek forms have no initial consonant, as Classical Greek really has neither /w/ nor /v/

“(4) There are other [w~v] or <w>~<v> families, like Latin <vert~verse> and Germanic <wr> (wring, wrist, wrench, etc). Or Latin <vace> (vacuum, vacation, evacuate), French void, and Germanic want, wane. Definitely there are others.

“But I think here is the biggest, non-etymological take-away,” I wrapped up. “Whenever you have two consecutive vowel letters that are NOT a digraph — in other words, they are pronounced separately in any member of the morphological family — you should expect that the two vowels have a plus sign between them. For example:

< ide + a >

< rue + in >

< frue + it + ion >

< cre + ate >

“Sometimes it can be hard to tell when there is a liquid <l> or <r> involved. For example, in the words dual, duel, fuel, cruel. Are they one or two syllables, one or two morphemes? You have to look at the family:

< du + o, du + al, du + el >

< cru + el, e + cru >

< fuel > is like < fire > — two phonetic syllables but one phonological.

“The only two words I know of that have separately-pronounced vowels that cannot be morphologically separated are meander and oceanic, both of which are eponyms.

“I know that’s a lot of info. As always, no need to teach it all, and I’m here to help!”

Now, wasn’t it wise of her to ask?